American Meteorite Survey

American Meteorite SurveySchoner's

American Meteorite Survey

American Meteorite Survey

Meteorite Identification Page

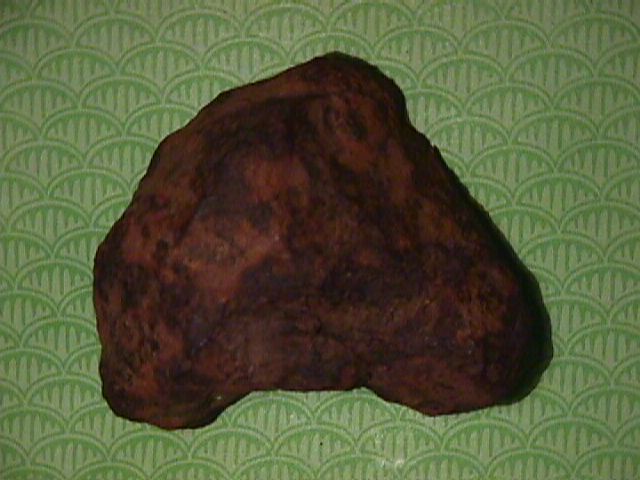

Because the earth's crust is so rich in iron oxides and iron minerals, meteorite identification is a daunting task for the layman, and even the professional geologist. For over twenty years the American Meteorite Survey has endeavored to find, catalog and distribute meteorites to institutions and collectors. We invite the submission of suspected meteorite samples for identification and appraisal. But in this task very few samples submitted turn out to be meteoric. The average is about one in a thousand. The purpose of this page is to present information that will better aid the reader to recognize meteorites.

SO you think that you may have found a meteorite?

But how can you be sure?

Does your suspected space rock fit the following criteria?

Campos Sales, Brazil; L-5,(stone), Fell Jan 31, 1991. This 96 gram full slice is from a stone that was picked up shortly after a bright meteor was sighted. Notice the white malleable metal grains in this expertly cut specimen.

Lamont, Kansas; Mesosiderite, (stony-iron)70.6 grams. Notice the numerous iron-nickel inclusions scattered throughout a stony matrix in a nearly 50-50 mix.

Canyon Diablo, Arizona, ("Meteor Crater")iron meteorite, 245 g. In this specimen cut lenghtwise the solid malleable metal interior is revealed.

Toluca, Mexico, iron meteorite, 658 grams. This meteorite has a thick oxide coating that flakes away. Inside it is solid metal.

Macy, NM; L-6 (weathered stone), 368 grams. Notice the tan-brown surface with dark brown patches of fusion crust.

Campos Sales, L-5 (stone), 571 grams. Notice the dark smooth fusion crust, and lighter chalky interior matrix that is speckled with rust spots.

Campos Sales, Brazil, L-5, (stone) 960 grams. Notice the exceptional black fusion crust and thumbprints on this very fine specimen. The light patches are where the fusion crust was broken on impact, thus revealing this meteorite's light gray chalky stone interior. The broken surfaces are speckled with rust spots where atmospheric moisture has caused the malleable iron grains to discolor an otherwise mostly light gray matrix. This specimen was picked up very shortly after falling to earth on Jan. 31st, 1991 and is typical of most freshly fallen meteorites.

Glorieta Mountain, NM; Siderite (iron), 320 grams. Notice the "thumbprints" on this exceptionally beautiful specimen. Also present are traces of blue-black fusion crust. A space rock like this is too nice to cut or grind. But inside it looks like steel.

Often I receive rocks that the finder swears they saw strike the ground. They are adamant that the fireball plunged to the ground when they say:

"I saw a meteor flaming all the way to the ground last night and when I went out to look for it, I found this in the spot where it hit"

A fireball (bolide) was observed, but if anyone saw it burning all the way to the ground (horizon) it was actually many, many hundreds of miles away. The terminus of these events is usually about 15 to 20 miles above the earth, and at that point the "burning" phase ends with huge explosion, or simply fades out. But if it hit burning all the way to the ground an explosion akin to that of an atomic bomb would surely be the result. The amount of kinetic energy in meteoroid traveling at 7 to 30 or more miles per second is enormous. Fortunately, our planet's thick blanket of air protects its surface (and us) from constant bombardment. If this were not so then even a small pea sized rock or chunk of iron hitting the ground at 30 miles per second would explode with the force of a 500 lb bomb and create a crater yards in diameter. Our world would look like the moon if it were not for our atmosphere burning these cosmic interlopers up.

But such events do occur.

When a large enough object enters the atmosphere, and then reaches the grond with even a fraction of its cosmic velocity, cratering can be extensive. The Sikhote Alin event in the former USSR on Feb 12, 1947 was the last such recorded cratering event.

Fortunately, crater forming events are rare in terms of the scale of human history, and most of the meteorites that fall to earth simply plunge to the earth's surface innocuously. Freshly fallen meteorites if found at all are usually found beneath the track of observed fireballs, or directly under the point over the ground where the fireball terminated.

These freshly fallen meteorites, whether small or large will show (unless fragmented) some amount of fusion crust. This crust is usually dark gray to black, but in some instances such as in the rare Cumberland Falls Meteorite, Norton County Meteorite, and the Pena Blanca Springs Meteorite (observed falls) the fusion crust can look like a thin tan to dark brown varnish. Fusion crust is one of the primary characteristics that one should look for in the process of meteorite identification. Except for very weathered specimens most meteorites will have a fusion crust or traces of it, and learning to identify it is important in sorting out meteorites from "meteorwrongs"

Often after a fireball event people are excited enough to go out and look for meteorites. Previously fallen meteorites not related to the event that sparked one to search are sometimes found. Thus it pays to search for space rocks after a major fireball sighting.

So, if your rock meets most if not all of these meteorite identification points, then there is a fair chance that it is a genuine meteorite. You should then send it, or at least a postage sized piece of it to a university that specializes in meteorites or to an authority on meteorites, such as myself.

I offer meteorite identification services at no cost, other than a small sample and should your rock prove to be a meteorite, then I will also evaluate it and give you an idea as to what it is worth.

Email:

Steve Schoner

American Meteorite Survey

P. O. Box 1003

Flagstaff, AZ 86002

METEORITE PICTURE GALLERY

:(Click on the highlighted "htm" file then use "back" option in your browser to close the pictures and return to this page)

STONES:

CORREO, NEW MEXICO CORREO.htm

GOLD BASIN, ARIZONA

GOLDBASIN.htmHOLBROOK, ARIZONA

HOLBROOK.htmLAFAYETTE, INDIANA

LAFAYETTE.htm

STONY-IRONS:

GLORIETA MOUNTAIN, NM

GLORIETA.htmLAMONT, KS

LAMONT.htmQUIJINQUE, BRAZIL

QUIJINGUE.htm

IRONS:

CANYON DIABLO

CANYON DIABLO.htmBRENHAM, KS

BRENHAM.htm(more photos will be added in the near future.)

THE NATURE OF METEORITES

(Under development. Please return at a later date)

Copyright Steven R. Schoner 2000